Science

과학(Science)은 우주(universe)에 대한 테스트-가능한(testable) 설명(explanations)과 예측(predictions)의 형식에서 지식(knowledge)을 빌드(builds)하고 조직하는 시스템인 엔터프라이스입니다.[1][2]

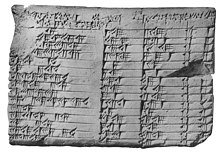

과학은 인간 종(human species)만큼 오래되었을 수 있고,[3] 과학적 추론에 대한 가장 오래된 고고학적 증거 중 일부는 수만 년 전입니다.[4] 과학의 역사(history of science)에서 가장 초기 기록은 기원전(BCE) 약 3000년에서 1200년에서 고대 이집트(Ancient Egypt)와 메소포타미아(Mesopotamia)로 거슬러 올라갈 수 있습니다.[5][6] 수학(mathematics), 천문학(astronomy), 및 의학(medicine)으로의 그들의 공헌은 고전 유물(classical antiquity)의 그리스 자연 철학(natural philosophy)에 들어가고 형성했으며, 이로써 자연적 원인에 기초하여 물리적 세계(physical world)의 사건에 대한 설명을 제공하려는 공식적인 시도가 이루어졌습니다.[5][6] 서로마 제국의 멸망 후에, 중세(Middle Ages) 초기 (기원후 400에서 1000년) 동안 서유럽(Western Europe)에서 그리스 세계관에 대한 지식이 쇠퇴했지만,[7] 이슬람 황금 시대(Islamic Golden Age) 동안 이슬람 세계(Muslim world)에서 보존되었습니다.[8]

10세기부터 13세기까지 그리스 연구(Greek works)의 회복과 동화와 서유럽으로의 이슬람의 탐구(Islamic inquiries)는 "자연 철학(natural philosophy)"을 부활시켰으며,[7][9] 그것은 새로운 아이디어와 발견이 이전의 그리스 개념과 전통에서 벗어나면서 16세기에 시작된 과학 혁명(Scientific Revolution)에 의해 나중에 변형되었습니다.[10][11][12] 과학적 방법(scientific method)은 곧 지식 창조에서 더 큰 역할을 했고 과학의 많은 제도적(institutional)이고 전문적(professional) 특징이 형성되기 시작한 것은, "자연 철학"에서 "자연 과학"으로의 변화와 함께,[13] 19세기가 되어서야 이루어졌습니다.[14][15]

현대 과학은 전형적으로 세 가지 주요 분야:[16] 물리적 세계(physical world)를 연구하는 자연 과학(natural sciences) (예를 들어, 생물학(biology), 화학(chemistry), 및 물리학(physics)); 개인(individuals)과 사회(societies)를 연구하는 사회 과학(social sciences) (예를 들어, 경제학(economics), 심리학(psychology), 및 사회학(sociology));[17][18] 및 공리(axioms)와 규칙에 의해 지배된 형식 시스템(formal systems)을 연구하는 형식 과학(formal sciences) (예를 들어, 논리(logic), 수학(mathematics), 및 이론적 컴퓨터 과학(theoretical computer science))으로 나뉩니다.[19][20] 형식 과학이 과학 분야인지 여부에 대해서는 이견이 있는데,[21][22][23] 왜냐하면 그것들이 경험적 증거(empirical evidence)에 의존하지 않기 때문입니다.[24][22] 응용 과학(Applied sciences)은 공학(engineering)과 의학(medicine)과 같은 실용적인 목적을 위해 과학적 지식을 사용하는 학문입니다.[25][26][27]

과학에서 새로운 지식은 세상에 대한 호기심과 문제 해결에 대한 열망으로 동기를 부여받은 과학자들(scientists)의 연구(research)에 의해 발전됩니다.[28][29] 현대 과학 연구는 고도로 협력적이고 보통 학계(academic)와 연구 기관(research institutions),[30] 정부 기관(government agencies), 및 회사(companies)의 팀에 의해 수행됩니다.[31][32] 그들의 연구의 실질적인 영향은 상업 제품(commercial products), 군장비(armaments), 의료(health care), 공공 기반-시설(public infrastructure), 및 환경 보호(environmental protection)의 개발을 우선시함으로써 과학 엔터프라이스에 영향을 미치려는 과학 정책(science policies)의 출현으로 이어져 왔습니다.

Etymology

단어 science는 14세기부터 중세 영어에서 "앎의 상태"라는 의미로 사용되어 왔습니다. 그 단어는 접미사 -cience로 앵글로-노르만 언어에서 차용되었으며, 이는 "지식, 인식, 이해"를 의미하는 라틴 단어 scientia에서 차용되었습니다. 그것은 "앎"을 의미하는 라틴어 sciens에서 명사 파생어이고, 논쟁의 여지없이 "아는 것"을 의미하는 현재 분사 scīre, 라틴어 sciō에서 파생되었습니다.[33]

science'의 궁극적인 어원에 대해서는 많은 가설이 있습니다. 네덜란드 언어학자이자 인도-유럽학자, Michiel de Vaan에 따르면, sciō는 Proto-Italic language이탈리아조어에서 "아는 것"을 의미하는 *skije- 또는 *skijo-로 그것의 기원을 가질 수 있으며, 이는 인도유럽조어에서 "절개하는 것"을 의미하는 *skh1-ie, *skh1-io로 유래할 수 있습니다. Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben는 sciō는 "알지 못하는 것, 익숙하지 않은"을 의미하는 nescīre의 역형성이라고 제안했으며, 이는 "자르는 것"을 의미하는 *sḱʰeh2(i)-에서 라틴어 secāre에서 인도유럽조어 *sekH-에서 파생될 수 있습니다.[34]

과거에, 과학은 라틴어 기원에 따라 "지식" 또는 "연구"에 대해 동의어였습니다. 과학적 연구를 수행한 사람은 "자연 철학자" 또는 "과학의 남자"라고 불렸습니다.[35]: 3–15 1833년에, 윌리엄 휴얼(William Whewell)은 scientist라는 용어를 만들었고 그 용어는 1년 후 메리 서머빌(Mary Somerville)의 Quarterly Review에 출판된 On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences에서 처음 나타났습니다.[36]

History

Earliest roots

과학에는 단일 기원을 가지지 않습니다. 오히려, 과학적 방법은 수천 년에 걸쳐 점진적으로 등장, 전 세계적으로 다양한 형태를 취했고, 가장 초기의 발전에 대해서는 알려진 바가 거의 없습니다. 과학적 추론에 대해 가장 초기의 증거 중 일부는 수만 년 전의 것이고,[4] 여성은 종교 의식에서 했던 것처럼[37] 선사시대 과학에서 중요한 역할을 했습니다.[38] 일부 서양 저자들은 이들 노력을 "원형과학(protoscientific)"이라고 일축했습니다.[39]

과학적 과정에 대한 직접적인 증거는 고대 이집트와 메소포타미아와 같은 초기 문명에서 쓰기 시스템(writing systems)의 출현으로 더욱 분명해졌습니다.[5] "과학"과 "자연"이라는 단어와 개념은 그 당시 개념적 배경의 일부가 아니었지만, 고대 이집트인과 메소포타미아인은 나중에 그리스와 중세 과학:수학, 천문학, 의학에서 자리를 찾을 공헌을 했습니다.[40][5] 기원전 3000년부터, 고대 이집트인들은 십진 숫자-세는 시스템(decimal numbering system)을 개발했고,[41] 기하학(geometry)을 사용하여 실용적인 문제를 해결했고,[42] 달력(calendar)을 개발했습니다.[43] 그들의 치유 요법에는 약물 치료와 기도(prayers), 주문(incantations), 및 의식과 같은 초자연적 현상을 포함했습니다.[5]

고대 메소포타미아인들은 도자기(pottery), 파이앙스(faience), 유리, 비누, 금속, 석회 석고(lime plaster), 및 방수를 제조하기 위해 다양한 천연 화학 물질의 속성에 대한 지식을 사용했습니다.[44] 그들은 점술(divinatory) 목적으로 동물 생리학(animal physiology), 해부학(anatomy), 행동학(behavior), 및 점성학(astrology)을 연구했습니다.[45] 메소포타미아인들은 의학에 깊은 관심을 가지고 있었고[44] 최초의 의약 처방(medical prescription)은 우르 제3왕조 동안 수메르어(Sumerian)로 나타났습니다.[46] 그들은 실용적이거나 종교적으로 응용되고 호기심을 충족시키는 데 거의 관심이 없는 과학적 주제를 연구하는 것 같습니다.[44]

Classical antiquity

고전 유물(classical antiquity)에서, 현대 과학자(scientist)의 실제 고대 아날로그는 없습니다. 대신, 교육을 잘 받았고, 보통 상류층이고, 거의 보편적으로 남성이 시간이 날 때마다 자연에 대한 다양한 조사를 수행했습니다.[47] 소크라테스-이전 철학자(pre-Socratic philosopher)들에 의해 phusis 또는 자연의 개념(concept)을 발명하거나 발견하기 전에, 같은 단어가 식물이 자라는 자연적인 "방법"과[48] 예를 들어, 한 부족은 특정 신을 숭배하는 "방법"을 설명하기 위해 사용되는 경향이 있었습니다. 이러한 이유로, 이들 남자들은 엄밀한 의미에서 최초의 철학자이자 "자연"과 "관습"을 명확하게 구분한 최초의 철학자라고 주장됩니다.[49]: 209

밀레토스의 탈레스(Thales of Miletus)에 의해 설립되고 나중에 그의 후계자 아낙시만더(Anaximander)와 아낙시메네스(Anaximenes)에 의해 계승되었던 밀레시안 학파(Milesian school)의 초기 그리스 철학자들(Greek philosophers)은 초자연적 현상(supernatural)에 의존 없이 자연 현상(natural phenomena)을 설명하려고 시도한 최초의 사람들이었습니다.[50] 피타고라스 학파(Pythagoreans)는 복잡한 숫자 철학을 개발했었고[51]: 467–68 수학적 과학의 발전에 크게 공헌했습니다.[51]: 465 원자 이론(theory of atoms)은 그리스 철학자 루시퍼스(Leucippus)와 그의 제자 데모크리토스(Democritus)에 의해 개발되었습니다.[52][53] 그리스 의사 히포크라테스(Hippocrates)는 시스템적 의학의 전통을 확립했었고[54][55] "의학의 아버지(The Father of Medicine)"로 알려져 있습니다.[56]

초기 철학적 과학의 역사에서 전환점은 인간 본성, 정치 공동체의 본성과 인간 지식 자체를 포함한 인간 문제의 연구에 철학을 적용한 소크라테스(Socrates)의 사례였습니다. 플라톤(Plato)의 대화에 의해 문서화된 소크라테스식 방법(Socratic method)은 가설 제거의 변증법적(dialectic) 방법입니다: 더 나은 가설은 모순으로 이어지는 것을 꾸준히 식별하고 제거함으로써 발견됩니다. 소크라테스식 방법은 신념을 형성하고 일관성을 위해 그것들을 조사하는 공통적으로-통용되는 진리를 검색합니다.[57] 소크라테스는 이전 유형의 물리학 연구를 너무 순전히 사색적이고 자기-비판(self-criticism)에서 결여를 비판했습니다.[58]

기원전 4세기에서 아리스토텔레스(Aristotle)는 목적론적(teleological) 철학의 시스템적인 프로그램을 만들었습니다.[59] 기원전 3세기에서, 그리스 천문학자 사모스의 아리스타르코스(Aristarchus of Samos)는 태양이 중심에 있고 모든 행성이 그 주위를 도는 우주의 태양-중심적 모델(heliocentric model)을 최초로 제안했습니다.[60] 아리스타르코스의 모델은 물리 법칙을 위반하는 것으로 여겨졌기 때문에 널리 거부되었지만,[60] 태양 시스템(Solar System)의 지구 중심적 설명을 포함하는 프톨레마이오스(Ptolemy)의 Almagest는 초기 르네상스를 통해 대신 받아들여졌습니다.[61][62] 발명가이자 수학자 시라쿠사의 아르키메데스(Archimedes of Syracuse)는 미적분학(calculus)의 시작에 큰 공헌을 했습니다.[63] 대 플리니우스(Pliny the Elder)는 로마의 작가이자 철학자로서 획기적인 Natural History 백과사전을 저술했습니다.[64][65][66]

Middle Ages

서로마 제국의 멸망(collapse of the Western Roman Empire)으로 인해, 5세기는 서유럽에서 지적 쇠퇴를 보였습니다.[67]: 307, 311, 363, 402 이 기간 동안, 세비야의 이시도르(Isidore of Seville)와 같은 라틴 백과사전은 일반 고대 지식의 대부분을 보존했습니다.[68] 대조적으로, 비잔틴 제국(Byzantine Empire)은 침략자들의 공격에 저항했기 때문에, 그들은 선행 학습을 보존하고 향상시킬 수 있었습니다. 500년대의 비잔틴 학자, 존 필로포누스(John Philoponus)는 아리스토텔레스의 물리학의 가르침에 의문을 제기하기 시작했고, 그것의 결점을 지적합니다.[67]: 307, 311, 363, 402 그의 비판은 중세 학자와 갈릴레오 갈릴레이에게 영감을 주었으며, 그들은 십 세기 후에 그의 연구를 광범위하게 인용했습니다.[67][69]

고대 후기(late antiquity)와 중세 초기(early Middle Ages) 동안, 주로 아리스토텔레스적 접근을 통해 자연 현상을 조사했습니다. 그 접근 방식은 아리스토텔레스의 네 가지 원인: 물질적 원인, 형식적 원인, 움직이는 원인, 및 최종 원인을 포함합니다.[70] 많은 그리스 고전 텍스트는 비잔틴 제국(Byzantine empire)에 의해 보존되었고 아랍어 번역은 Nestorians와 Monophysites와 같은 그룹에 의해 수행되었습니다. Caliphate 아래에서, 이들 아랍어 번역은 나중에 아랍 과학자들에 의해 개선되고 발전되었습니다.[71] 6세기와 7세기에, 이웃한 사산 제국(Sassanid Empire)은 곤데샤푸르 아카데미(Academy of Gondeshapur)를 설립했으며, 그리스, 시리아, 및 페르시아 의사들에 의해 고대 세계의 가장 중요한 의료 중심지로 여겼습니다.[72]

지혜의 집(House of Wisdom)은 이라크의 아바시드-시대 바그다드에 설립되었으며,[73] 여기서 아리스토텔레스주의(Aristotelianism)에 대한 이슬람 연구는 13세기에 몽골 침략 때까지 번성했습니다.[74] 알하젠으로 더 잘 알려진 이븐 알-하이삼(Ibn al-Haytham)은 지식을 얻기 위한 수단으로 실험을 시작했고[75][76] 프톨레마이오스의 시각 이론(Ptolemy's theory of vision)을 반증했습니다.[77]: Book I, [6.54]. p. 372 아비세나(Avicenna)의 의학 백과사전, 의학의 정경(Canon of Medicine) 편집은 의학에서 가장 중요한 출판물 중 하나로 고려되고 18세기까지 사용되었습니다.[78]

11세기에 이르러, 유럽의 대부분은 기독교 국가가 되었고,[7] 1088년에서 볼로냐 대학교(University of Bologna)가 유럽 최초의 대학교로 부상했습니다.[79] 이와 같이, 고대와 과학 텍스트의 라틴어 번역에 대한 수요가 증가했으며,[7] 이는 12세기 르네상스의 주요 공헌자였습니다. 서유럽에서 르네상스 스콜라주의(scholasticism)는 자연의 주제를 관찰하고, 기술하고, 분류하는 실험을 통해 번성했습니다.[80] 13세기에 볼로냐의 의학 교사와 학생들은 인체를 개방하기 시작하여, Mondino de Luzzi에 의한 인체 해부에 기초한 최초의 해부학 교과서로 이어졌습니다.[81]

Renaissance

광학에서 새로운 발전은 인식에 대한 오랜 형이상학적(metaphysical) 아이디어에 도전하고, 암실(camera obscura)과 망원경(telescope)과 같은 기술의 개선과 발전에 기여함으로써 르네상스(Renaissance)의 시작에 중요한 역할을 했습니다. 르네상스 초기에, Roger Bacon, Vitello, 및 John Peckham은 각각 아리스토텔레스의 개별적이고 보편적인 형식(forms)에 대한 감각, 지각, 및 최종적으로 통각으로 시작하는 인과 관계에 대한 스콜라적 존재론(ontology)을 구축했습니다.[77]: Book I 훗날 원근주의(perspectivism)로 알려진 시각의 모델은 르네상스 시대의 예술가들에 의해 개척되고 연구되었습니다. 이 이론은 아리스토텔레스의 네 가지 원인중 세 가지: 형식적 원인, 물질적 원인, 및 최종 원인만을 사용합니다.[82]

16세기에, 니콜라우스 코페르니쿠스(Nicolaus Copernicus)는 행성과 태양이 지구 주위를 공전하는 지구-중심 모델(geocentric model) 대신에 행성이 태양 주위를 돈다는 태양 시스템의 태양-중심 모델(heliocentric model)을 공식화했습니다. 이것은 행성의 궤도 주기(orbital periods)는 궤도가 운동의 중심에서 멀어질수록 더 길다는 정리를 기반으로 했으며, 이는 프톨레마이오스의 모델과 일치하지 않는다는 것을 발견했습니다.[83]

요하네스 케플러(Johannes Kepler)와 다른 사람들은 눈의 유일한 기능은 지각이라는 개념에 도전했고, 광학에서 주요 초점을 눈에서 빛의 전파로 옮겼습니다.[82][84] 케플러는 어쨌든 케플러의 행성 운동 법칙(Kepler's laws of planetary motion)의 발견을 통해 코페르니쿠스의 태양-중심 모델을 개선한 것으로 가장 잘 알려져 있습니다. 케플러는 아리스토텔레스의 형이상학을 거부하지 않았고 그의 연구를 구체의 조화(Harmony of the Spheres)에 대한 탐색으로 묘사했습니다.[85] 갈릴레오(Galileo)는 천문학, 물리학, 및 공학에 상당한 공헌을 했습니다. 어쨌든, 그는 교황 우르바노 8세가 태양 중심 모델에 대해 글을 쓴 죄로 그에게 선고를 내린 후 박해를 받게 되었습니다.[86]

인쇄기(printing press)는 자연의 현대적 아이디어에 크게 동의하지 않는 일부를 포함하여 학문적 주장을 출판하기 위해 널리 사용되었습니다.[87] 프랜시스 베이컨(Francis Bacon)과 르네 데카르트(René Descartes)는 새로운 유형의 비-아리스토텔레스적 과학을 지지하는 철학적 논증을 발표했습니다. 베이컨은 관조보다 실험의 중요성을 강조했고, 형식적 원인과 최종 원인에 대한 아리스토텔레스의 개념에 의문을 제기했으며, 과학은 자연의 법칙(laws of nature)과 모든 인간 삶의 개선을 연구해야 한다는 생각을 장려했습니다.[88] 데카르트는 개인의 생각을 강조했고 기하학보다 수학이 자연을 연구하기 위해 사용되어야 한다고 주장했습니다.[89]

Age of Enlightenment

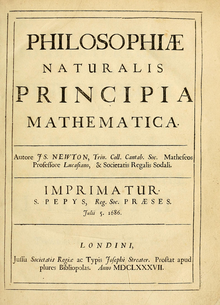

계몽주의 시대(Age of Enlightenment)의 시작에서, 아이작 뉴턴(Isaac Newton)은 Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica에 의해 고전 역학의 토대를 형성했으며, 미래 물리학자들에게 지대한 영향을 미쳤습니다.[90] 고트프리트 빌헬름 라이프니츠(Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz)는 아리스토텔레스 물리학(Aristotelian physics)에서 용어를 통합했으며, 이제 새로운 비-목적론적(teleological) 방식으로 사용됩니다. 이것은 대상에 대한 관점의 변화를 의미합니다: 대상은 이제 타고난 목표가 없는 것으로 고려됩니다. 라이프니츠는 특별한 형식적 원인 또는 최종 원인을 가지지 않는 다양한 유형의 사물이 모두 같은 일반적인 자연의 법칙에 따라 작동한다고 가정했습니다.[91]

이 기간 동안, 과학의 선언된 목적과 가치는 더 많은 음식, 의복, 및 기타 물건을 더 많이 가지는 물질적(materialistic) 의미에서 인간의 삶을 향상시킬 부와 발명품(inventions)을 생산하는 것이 되었습니다. 베이컨의 말에 따르면, "과학의 실제적이고 합법적인 목표는 인간의 삶에 새로운 발명품과 부를 부여하는 것"이고 그는 과학자들에게 무형의 철학적 또는 영적 아이디어를 추구하는 것을 권장하지 않았으며, 그는 "미묘하고 숭고하거나 유쾌한 [추측]의 연기" 외에는 인간의 행복에 거의 기여하지 않는다고 믿었습니다.[92]

계몽주의 시대 동안 과학은 과학 연구와 개발의 중심지로서 대학교를 크게 대체해 왔던 과학 사회(scientific societies)와[93] 아카데미(academies)에 의해 지배되었습니다. 사회와 아카데미는 과학 직업의 성숙의 중추였습니다. 또 다른 중요한 발전은 점차 증가하는 문맹 인구 중에서 과학의 대중화(popularization)였습니다.[94]: 82–83 계몽주의 철학자들은 과학의 전임자 – 갈릴레오(Galileo), 보일(Boyle), 및 주로 뉴턴 –의 짧은 역사를 그 당시 과학의 모든 각 물리적, 사회적 분야에 대한 안내자로 선택했습니다.[95]

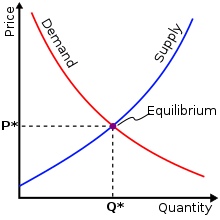

18세기는 의학(medicine)과[96] 물리학(physics)의[97] 실제 적용에서 상당한 발전을 보였습니다; 칼 린네(Carl Linnaeus)에 의한 생물학적 분류법(taxonomy)의 발전;[98] 자기학(magnetism)과 전기학(electricity)의 새로운 이해;[99] 및 학문으로서의 화학(chemistry)의 성숙을 보였습니다.[100]: 265 인간의 본성, 사회, 및 경제에 대한 아이디어는 계몽주의 기간 동안 발전했습니다. 흄(Hume)과 다른 스코틀랜드 계몽주의 사상가들은 현대성(modernity)의 결정적인 힘에 대한 강한 인식과 함께 고대와 원시 문화에서 인간이 어떻게 행동했는지에 대한 과학적 연구를 통합했던 제임스 버넷(James Burnett), 아담 퍼거슨(Adam Ferguson), 존 밀러(John Millar), 및 윌리엄 로버트슨(William Robertson)을 포함한 작가들에 의해 연구에서 역사적으로 표현되었던 A Treatise of Human Nature을 개발했습니다.[101] 현대 사회학은 주로 이 운동에서 비롯되었습니다.[102] 1776년, 아담 스미스는 현대 경제학의 첫 번째 저작으로 여겨지는 국부론(The Wealth of Nations)을 출판했습니다.[103]

19th century

19세기 동안, 같은 시대의 현대 과학의 많은 두드러진 특징이 형성되기 시작했습니다. 그 중 일부는 생명 과학과 물리적 과학의 변화, 정밀 기기의 빈번한 사용, "생물학자", "물리학자", "과학자"와 같은 용어의 출현, 자연을 연구하는 사람들의 증가된 전문화, 사회의 다방면에 걸쳐 문화적 권위를 획득한 과학자들, 수많은 국가의 산업화, 대중적인 과학 저술의 번성과 과학 저널의 출현이 있습니다.[104] 19세기 후반 동안, 심리학(psychology)은 빌헬름 분트(Wilhelm Wundt)가 1879년에 심리학 연구를 위한 최초의 실험실을 설립했을 때 철학과 별개의 학문으로 등장했습니다.[105]

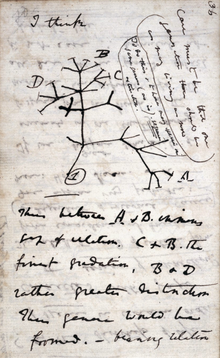

19세기 중반 동안, 찰스 다윈(Charles Darwin)과 알프레드 러셀 월레스(Alfred Russel Wallace)는 1858년에 자연 선택(natural selection)에 의한 진화론을 독립적으로 제안하여, 다양한 식물과 동물이 어떻게 기원하고 진화했는지 설명했습니다. 그들의 이론은 1859년에 출판된 다윈의 책 종의 기원(On the Origin of Species)에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다.[106] 이와 별도로, 그레고르 멘델(Gregor Mendel)은 1865년에 "식물 교잡에 대한 실험(Experiments on Plant Hybridization)"이라는 논문을 발표했으며,[107] 이는 현대 유전학의 기초가 되는 생물학적 유전의 원리를 설명했습니다.[108]

19세기 초, 존 달튼(John Dalton)은 원자(atoms)라고 하는 쪼갤 수 없는 입자의 데모크리토스(Democritus)의 원래 아이디어에 기초된 현대 원자 이론(atomic theory)을 제안했습니다.[109] 에너지 보존(conservation of energy), 운동량 보존(conservation of momentum), 및 질량 보존(conservation of mass)의 법칙은 자원 손실이 거의 없는 매우 안정적인 우주를 제안했습니다. 어쨌든, 증기 기관(steam engine)의 도래와 산업 혁명(industrial revolution)과 함께, 모든 형태의 에너지가 같은 에너지 특질(energy qualities)을 갖는 것은 아니며, 유용한 일(work) 또는 또 다른 형태의 에너지로의 전환이 용이하다는 이해가 증가했습니다.[110] 이 깨달음은 우주의 자유 에너지가 끊임없이 감소한다: 닫힌 우주의 엔트로피(entropy)는 시간이 지남에 따라 증가한다는 것으로 보이는 열역학(thermodynamics) 법칙의 발전으로 이어졌습니다.[a]

전자기 이론은 Hans Christian Ørsted, André-Marie Ampère, Michael Faraday, James Clerk Maxwell, Oliver Heaviside, 및 Heinrich Hertz의 연구에 의해 19세기에 확립되었습니다. 새로운 이론은 뉴턴의 틀을 사용하여 쉽게 대답될 수 없는 질문을 제기했습니다. X-선(X-rays)의 발견은 1896년 Henri Becquerel와 Marie Curie에 의한 방사능(radioactivity) 발견에 영감을 주었으며,[113] Marie Curie는 그 다음에 두 개의 노벨상(Nobel prizes)을 받은 최초의 사람이 되었습니다.[114] 다음 해에 최초의 아원자 입자인 전자(electron)가 발견되었습니다.[115]

20th century

20세기 전반부에, 항생제(antibiotics)와 인공 비료(artificial fertilizers)의 개발은 전 세계적으로 인간의 생활 수준(living standards)을 향상시켰습니다.[116][117] 오존층 파괴(ozone depletion), 해양 산성화(ocean acidification), 부영양화(eutrophication), 및 기후 변화(climate change)와 같은 유해한 환경 문제가 대중의 관심을 얻게 되고 환경 연구(environmental studies)의 시작을 초래했습니다.[118]

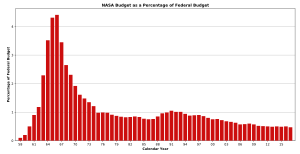

이 기간 동안, 과학 실험의 규모와 자금은 점점 더 커졌습니다.[119] 제1차 세계 대전, 제2차 세계 대전, 및 냉전으로 촉발된 광범위한 기술 혁신은 우주 경쟁(Space Race)[120]: 3–5 및 핵무기 경쟁(nuclear arms race)과 같은 세계 강대국(global powers) 사이의 경쟁으로 이어졌습니다.[121] 무력 충돌에도 불구하고, 상당한 국제 협력도 이루어졌습니다.[122]

20세기 말에서, 여성의 적극적인 모집과 성 식별(sex discrimination) 철폐로 여성 과학자의 수는 크게 늘었지만, 일부 분야에서는 성 격차가 크게 남아 있었습니다.[123] 1964년 우주 마이크로파 배경(cosmic microwave background)의 발견은[124] 조르주 르메트르(Georges Lemaître)의 빅뱅(Big Bang) 이론에 찬성하여 우주의 정상 상태 모델을 거부하도록 이끌었습니다.[125]

그 세기는 과학 분야에서 근본적인 변화를 보였습니다. 진화론은 현대 종합(modern synthesis)이 고전 유전학(classical genetics)과 다윈의 진화를 조화시킨 20세기 초에 통일된 이론이 되었습니다.[126] 알베르트 아인슈타인(Albert Einstein)의 상대성 이론(theory of relativity)과 양자 역학(quantum mechanics)의 발전은 고전 역학을 극단적인 길이(length), 시간(time), 및 중력(gravity)으로 물리학을 설명하기 위해 보완합니다.[127][128] 20세기 마지막 분기에 통신 위성(communications satellites)과 결합된 집적 회로(integrated circuits)의 광범위한 사용은 정보 기술(information technology)의 혁명과 스마트폰(smartphones)을 포함한 글로벌 인터넷(internet)과 모바일 컴퓨팅(mobile computing)의 부상으로 이어졌습니다. 길고 얽힌 인과 관계와 많은 양의 데이터의 대량 시스템화에 대한 필요성은 시스템 이론(systems theory)과 컴퓨터-지원 과학 모델링(scientific modeling) 분야의 부상으로 이어졌습니다.[129]

21st century

인간 게놈 프로젝트(Human Genome Project)는 인간 게놈(human genome)의 모든 유전자를 식별하고 매핑함으로써 2003년에 완료되었습니다.[130] 최초의 유도 만능 인간 줄기 세포(induced pluripotent human stem cells)는 2006년에 만들어졌으며, 성체 세포를 줄기 세포(stem cells)로 변형되고 신체에서 발견되는 모든 세포 유형으로 전환되는 것을 허용합니다.[131] 2013년 힉스 입자(Higgs boson) 발견이 확인되면서, 입자 물리학의 표준 모형(Standard Model)에 의해 예측된 마지막 입자가 발견되었습니다.[132] 2015년에, 1세기 전 일반 상대성(general relativity)에 의해 예측된 중력파(gravitational waves)가 처음으로 관측되었습니다.[133][134] 2019년에, 국제 협력 이벤트 호라이즌 망원경(Event Horizon Telescope)은 블랙홀(black hole)의 강착 디스크(accretion disk)의 첫 번째 직접 이미지를 발표했습니다.[135]

Branches

현대 과학은 공통적으로 자연 과학(natural science), 사회 과학(social science), 및 형식 과학(formal science)의 세 가지 주요 가지(branches)로 나뉩니다.[16] 이들 각 가지는 종종 그것들 자체의 명명법(nomenclature)과 전문 지식을 보유하는 다양히 전문화되지만 여전히 중복되는 과학 분야(disciplines)로 구성됩니다.[136] 자연 과학과 사회 과학은 모두 경험 과학(empirical sciences)인데,[137] 왜냐하면 그들의 지식은 경험적 관찰(empirical observations)을 기반으로 하고 같은 조건 아래에서 연구하는 다른 연구자에 의해 그 타당성에 대해 테스트될 수 있기 때문입니다.[138]

Natural science

자연 과학(Natural science)은 물리적 세계에 대한 연구입니다. 그것은 생명 과학(life science)과 물리적 과학(physical science)의 두 가지 주요 가지로 나뉠 수 있습니다. 이들 두 가지는 더 전문화된 분야로 더 나뉠 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 물리적 과학은 물리학(physics), 화학(chemistry), 천문학(astronomy), 및 지구 과학(earth science)으로 세분화될 수 있습니다. 현대 자연 과학은 고대 그리스(Ancient Greece)에서 시작된 자연 철학(natural philosophy)의 계승자입니다. 갈릴레오(Galileo), 데카르트(Descartes), 베이컨(Bacon), 및 뉴턴(Newton)은 보다 수학적(mathematical)이고 방법론적으로 더 실험적인 접근 방식으로 사용하는 것의 이점을 논의했습니다. 아직도, 종종 간과되는 철학적 관점, 추측(conjectures), 및 전제(presuppositions)는 자연 과학에서 여전히 필요성이 남아있습니다.[139] 발견 과학(discovery science)을 포함한 시스템적인 데이터 수집은 식물, 동물, 광물, 등을 기술하고 분류함으로써 16세기에 등장한 자연사(natural history)를 계승했습니다.[140] 오늘날, "자연사"는 대중적인 청중을 겨냥한 관찰 기술을 제안합니다.[141]

Social science

사회 과학(Social science)은 인간의 행동과 사회의 기능화에 대한 연구입니다.[17][18] 그것은 인류학(anthropology), 경제학(economics), 역사(history), 인문 지리학(human geography), 정치적 과학(political science), 심리학(psychology), 및 사회학(sociology)을 포함하지만 이에 국한되지 않는 많은 분야를 가집니다.[17] 사회 과학에서, 많은 경쟁적인 이론적 관점이 있으며, 그 중 많은 부분이 사회학에서 기능주의자(functionalists), 갈등 이론가(conflict theorists), 및 상호 작용론자(interactionists)와 같은 경쟁 연구 프로그램(research programs)을 통해 확장됩니다.[17] 개인의 큰 그룹이나 복잡한 상황을 포함하는 통제된 실험을 수행하는 것의 한계로 인해, 사회 과학자는 역사적 방법(historical method), 사례 연구(case studies), 및 교차-문화 연구(cross-cultural studies)와 같은 다른 연구 방법을 채택할 수 있습니다. 게다가, 양적 정보가 이용 가능하면, 사회 과학자들은 사회적 관계와 과정을 더 잘 이해하기 위해 통계적 접근에 의존할 수 있습니다.[17]

Formal science

형식 과학(Formal science)은 형식 시스템(formal systems)을 사용하여 지식을 생성하는 연구 분야입니다.[142][19][20] 형식 시스템은 규칙의 집합에 따라 공리(axioms)로부터 정리(theorems)를 추론하는 데 사용되는 추상 구조(abstract structure)입니다.[143] 그것은 수학(mathematics),[144][145] 시스템 이론(systems theory), 및 이론적인 컴퓨터 과학(theoretical computer science)을 포함합니다. 형식 과학은 지식 영역의 객관적이고, 세심하고, 시스템적인 연구에 의존함으로써 다른 두 가지와 유사점을 공유합니다. 그것들은, 어쨌든, 경험적 증거에 대한 필요성없이 그것들의 추상적인 개념을 검증하기 위해 연역적 추론에 배타적으로 의존한다는 점에서 경험적 과학과 다릅니다.[24][146][138] 형식 과학은 따라서 선험적(a priori) 학문이고 이 때문에, 그것들이 과학을 구성하는지 여부에 대한 의견 불일치가 있습니다.[21][147] 그럼에도 불구하고, 형식 과학은 경험 과학에서 중요한 역할을 합니다. 미적분학(Calculus)은, 예를 들어, 처음에 물리학에서 운동(motion)을 이해하기 위해 발명되었습니다.[148] 수학적 응용에 크게 의존하는 자연 과학과 사회 과학은 수학적 물리학(mathematical physics),[149] 화학(chemistry),[150] 생물학(biology),[151] 금융(finance),[152] 및 경제학(economics)을 포함합니다.[153]

Applied science

응용 과학(Applied science) 또는 기술(technology)은 실용적인 목표를 달성하기 위해 과학적 방법(scientific method)과 지식의 사용이고 공학(engineering)과 의학(medicine)과 같은 광범위한 분야를 포함합니다.[154][27] 공학은 기계, 구조, 및 기술을 발명, 설계, 및 구축하기 위해 과학적 원리의 사용입니다.[155] 의학은 부상이나 질병의 예방, 진단, 및 치료를 통해 건강을 유지하고 회복함으로써 환자를 돌보는 행위입니다.[156][157] 응용 과학은 종종 자연 세계에서 사건을 설명하고 예측하는 과학적 이론과 법칙을 발전시키는 데 중점을 둔 기초 과학(basic sciences)과 대조됩니다.[158][159]

계산 과학(Computational science)은 계산 능력을 실제 상황을 시뮬레이션하기 위해 적용하여, 형식 수학만으로 달성할 수 있는 것보다 과학적 문제를 더 잘 이해할 수 있도록 합니다. 기계 학습(machine learning)과 인공 지능(artificial intelligence)의 사용은 에이전트-기반 계산 경제학(agent-based computational economics), 랜덤 포레스트(random forests), 주제 모델링(topic modeling), 및 다양한 형태의 예측과 같은 과학에 대한 계산 기여의 핵심 기능이 되고 있습니다. 어쨌든, 기계만으로는 지식을 발전시키는 경우가 거의 없는데, 왜냐하면 그것들은 인간의 지도와 추론 능력을 요구하기 때문입니다; 그리고 그것들은 특정 사회 집단에 대한 편견을 불러일으키거나 때로는 인간에 대해 성과가 떨어질 수 있습니다.[160][161]

Interdisciplinary science

학제-상호 과학(Interdisciplinary science)은 생물 정보학(bioinformatics),[162] 생물학과 컴퓨터 과학의 결합과 같이 둘 이상의 학문을 하나로 결합하는 것을 포함합니다.[163]: vii 그 개념은 고대 그리스부터 존재해 왔고 20세기에 다시 대중화되었습니다.[164]

Scientific research

과학적 연구는 기초 연구 또는 응용 연구로 분류될 수 있습니다. 기초 연구(Basic research)는 지식에 대한 탐색이고 응용 연구(applied research)는 이 지식을 사용하여 실제적인 문제에 대한 해결책에 대해 검색입니다. 대부분의 이해는 기초 연구에서 이루어지지만, 때때로 응용 연구는 특정 실제 문제를 대상으로 합니다. 이것은 이전에는 상상할 수 없었던 기술 발전으로 이어집니다.[165]

Scientific method

과학적 연구는 자연(nature) 현상을 재현 가능한(reproducible) 방법으로 객관적(objectively)으로 설명하고자 하는 과학적 방법(scientific method)을 사용하는 것을 포함합니다.[166] 과학자들은 보통 과학적 방법을 정당화하는 데 필요한 일련의 기본 가정을 당연시합니다: 모든 합리적인 관찰자에 의해 공유되는 객관적인 현실(objective reality)이 있습니다; 이 객관적인 현실은 자연 법칙(natural laws)의 지배를 받습니다; 이들 법칙은 시스템적인 관찰과 실험을 수단으로 발견되었습니다.[167] 수학(Mathematics)은 정량적 모델링, 관찰과 측정 수집에 광범위하게 사용되기 때문에, 그것은 가설(hypotheses), 이론(theories), 및 법칙을 형성하는 데 필수적입니다.[168] 통계(Statistics)는 과학자들에게 실험 결과의 신뢰성을 평가할 수 있도록 데이터를 요약하고 분석하기 위해 사용됩니다.[169]

과학적 방법에서, 설명적 사고 실험이나 가설은 간결한 원칙(parsimony principles)을 사용하여 설명으로 제시되고 관찰 또는 과학적 질문과 관련하여 인정되는 다른 사실과 일치하는 부합(consilience)을 추구할 것으로 예상됩니다.[170] 이 잠정적인 설명은 전형적으로 실험에 의해 테스트되기 전에 게시되는 반증 가능한(falsifiable) 예측을 만들기 위해 사용됩니다. 예측의 반증은 진행의 증거입니다.[166]: 4–5 [171]: 204 실험은 과학에서 상관 오류(correlation fallacy)를 피하기 위해 인과 관계(causal relationships)를 설정하는 데 특히 중요하지만, 천문학이나 지질학(geology)과 같은 일부 과학에서 예측된 관찰이 더 적절할 수 있습니다.[172]

가설이 만족스럽지 않은 것으로 판명될 때, 그것은 수정되거나 폐기됩니다.[173] 가설이 테스트에서 살아남았다면, 그것은 과학적 이론(scientific theory)의 틀, 논리적으로 추론되고, 자체-일관된 모델 또는 특정 자연 사건의 행동을 설명하기 위한 틀로 채택될 수 있습니다. 이론은 전형적으로 가설보다 훨씬 광범위한 관찰 집합의 행동을 설명합니다; 공통적으로, 다수의 가설이 하나의 이론에 의해 논리적으로 함께 결합될 수 있습니다. 따라서 이론은 다양한 다른 가설을 설명하는 가설입니다. 그런 맥락에서, 이론들은 가설과 거의 같은 과학적 원리에 따라 공식화됩니다. 과학자들은 논리적, 물리적 또는 수학적 표현의 관점에서 관찰을 설명하거나 묘사하고 실험에 의해 테스트될 수 있는 새로운 가설을 생성하려는 시도하기 위한 모델(model)을 생성할 수 있습니다.[174]

가설을 테스트하기 위해 실험을 수행하는 동안, 과학자들은 또 다른 결과보다 한 결과를 선호할 수 있습니다.[175][176] 편견을 제거하는 것은 투명성, 신중한 실험 설계(experimental design), 및 실험 결과와 결론의 철저한 동료 검토(peer review) 과정을 통해 달성될 수 있습니다.[177][178] 실험 결과가 발표되거나 출판된 후, 독립적인 연구자에 대해 연구 수행 방법을 이중-확인하고, 결과가 얼마나 신뢰할 수 있는지 결정하기 위해 유사한 실험을 수행함으로써 후속 조치를 취하는 것이 통상적인 관행입니다.[179] 전체적으로 볼 때, 과학적 방법은 주관적이고 확증 편향(confirmation bias)의 영향을 최소화하면서 매우 창의적인 문제 해결을 가능하게 합니다.[180] 상호주관적 검증 가능성(Intersubjective verifiability), 합의에 도달하고 결과를 재현할 수 있는 능력은 모든 과학적 지식의 생성에 근본적입니다.[181]

Scientific literature

과학적 연구는 다양한 문헌에 발표되었습니다.[182] 과학 저널(Scientific journals)은 대학과 다른 다양한 연구 기관에서 수행된 연구 결과를 전달하고 문서화하여, 과학의 보관 기록 역할을 합니다. 최초의 과학 저널, Philosophical Transactions에 의한 Journal des sçavans는 1665년에 발행되기 시작했습니다. 그 이후로 활성 정기 간행물의 총 수가 꾸준히 증가해 왔습니다. 1981년에, 출판된 과학과 기술 저널 수에 대한 추정치는 11,500개였습니다.[183]

대부분의 과학 저널은 단일 과학 분야를 다루고 해당 분야 내의 연구를 출판합니다; 그 연구는 통상적으로 과학 논문(scientific paper)의 형식으로 표현됩니다. 과학은 과학자들의 업적, 소식, 및 야망을 더 많은 사람들에게 알리는 것이 필요하다고 여겨져서 현대 사회에 널리 퍼져 있습니다.[184]

Challenges

복제 위기(replication crisis)는 사회(social)와 생명 과학(life sciences)의 일부에 영향을 미치는 진행 중인 방법론적(methodological) 위기입니다. 후속 조사에서, 많은 과학적 연구 결과가 반복될 수 없음이 입증되었습니다.[185] 그 위기는 오랜 뿌리를 가지고 있습니다; 그 문구는 문제의 인식이 높아짐에 따라 2010년대 초에 만들어졌습니다.[186] 복제 위기는 낭비를 줄이면서 모든 과학적 연구의 질을 향상시키는 것을 목표로 하는 메타-과학(metascience)의 중요한 연구 기관을 나타냅니다.[187]

다른 방법으로는 달성할 수 없는 합법성을 주장하기 위한 시도에서 과학으로 가장하는 연구 또는 추측의 영역은 때때로 유사-과학(pseudoscience), 변두리 과학(fringe science), 또는 정크 과학(junk science)으로 참조됩니다.[188][189]: 17 물리학자 리처드 파인만(Richard Feynman은) 연구자들이 믿고 언뜻 보기에 과학을 하고 있는 것처럼 보이지만, 그것들의 결과를 엄격하게 평가할 수 있는 정직성이 결여되어 있는 경우에 대해 "화물 숭배 과학(cargo cult science)"이라는 용어를 만들었습니다.[190] 과대 광고에서 사기에 이르기까지 다양한 유형의 상업 광고가 이들 범주에 속할 수 있습니다. 과학은 유효한 주장과 무효한 주장으로부터 구분하는 "가장 중요한 도구"로 설명되어 왔습니다.[191]

역시 과학적 논쟁의 모든 측면에 정치적 또는 이념적 편향의 요소가 있을 수 있습니다. 때때로, 연구는 "나쁜 과학"으로 특징지어질 수 있으며, 그것은 의도는 좋지만 과학적 아이디어에 대한 부정확하거나, 쓸모없거나, 불완전하거나, 지나치게 단순화된 설명인 연구입니다. "과학적 부정행위(scientific misconduct)"라는 용어는 연구자가 의도적으로 출판된 데이터를 잘못 표현했거나 의도적으로 잘못된 사람에게 발견에 대한 공로를 부여한 상황을 의미합니다.[192]

Philosophy of science

과학의 철학(philosophy of science)에는 다양한 학파가 있습니다. 가장 인기 있는 입장은 지식이 관찰을 포함하는 과정에 의해 생성되고 과학적 이론은 그러한 관찰을 일반화한 결과라고 주장하는 경험주의(empiricism)입니다.[193] 경험주의는 일반적으로 사용 가능한 경험적 증거의 유한한 양에서 일반 이론이 만들어질 수 있는 방법을 설명하는 입장, 귀납주의(inductivism)를 포함합니다. 경험주의의 많은 버전이 존재하며, 우세한 버전은 베이즈주의(Bayesianism)와[194] 가설 연역법(hypothetico-deductive method)입니다.[193]

경험주의는 지식이 관찰에 의한 것이 아니라 인간 지성에 의해 생성된다고 주장하는 원래 데카르트(Descartes)와 관련된 입장, 합리주의(rationalism)와 대조를 이룹니다.[195] 비판적 합리주의(Critical rationalism)는 대조되는 20세기 과학에 대한 접근 방식으로, 처음으로 오스트리아-영국 철학자 칼 포퍼(Karl Popper)에 의해 정의되었습니다. 포퍼는 경험주의가 이론과 관찰 사이의 연결을 설명하는 방법을 거부했습니다. 그는 이론은 관찰에 의해 생성되는 것이 아니고, 관찰은 이론에 비추어 이루어지고 이론이 관찰에 의해 영향을 받을 수 있는 유일한 방법은 이론과 충돌할 때라고 주장했습니다.[196]

포퍼는 과학적 이론의 이정표로서 검증 가능성을 반증 가능성(falsifiability)으로 대체하고 경험적 방법으로 귀납법을 반증(falsification)으로 대체할 것을 제안했습니다.[196] 포퍼는 실제로 과학에만 국한되지 않은 보편적인 방법은 단 하나, 비판, 시행과 착오(trial and error)의 부정적인 방법이 있다고 주장했습니다.[197] 그것은 과학, 수학, 철학, 및 예술을 포함하여 인간 정신의 모든 산물을 다룹니다.[198]

또 다른 접근법, 도구주의(instrumentalism)는 현상을 설명하고 예측하는 도구로서의 이론의 유용성을 강조합니다. 그것은 과학 이론을 입력 (초기 조건)과 관련성이 있는 출력 (예측)만을 갖는 블랙박스로 봅니다. 결과, 이론적 실체, 및 논리적 구조는 무시되어야 하는 것으로 주장됩니다.[199] 도구주의에 가까운 것은 구성적 경험주의(constructive empiricism)이며, 이에 따르면 과학 이론의 성공에 대한 주요 기준은 관찰 가능한 실체에 대해 말하는 것이 사실인지 여부입니다.[200]

토마스 쿤(Thomas Kuhn)은 관찰과 평가의 과정이 패러다임, 그것의 프레임에서 만들어진 관찰과 일치하는 세계의 논리적으로 일관된(logically consistent) "초상" 내에서 발생한다고 주장했습니다. 그는 정규 과학(normal science)을 패러다임 내에서 발생하는 관찰과 "퍼즐 해결"의 과정으로 규정하고, 반면에 혁명적 과학(revolutionary science)은 패러다임 전환(paradigm shift)에서 한 패러다임이 또 다른 패러다임을 추월할 때 발생합니다.[201] 각 패러다임은 그것의 고유한 질문, 목표, 및 해석을 가집니다. 패러다임 사이의 선택은 세계에 대항하여 둘 이상의 "초상"을 설정하고 어떤 유사성이 가장 유망한지를 결정하는 것을 포함합니다. 패러다임 전환은 기존 패러다임에서 상당한 수의 관찰 이상 현상이 발생하고 새로운 패러다임이 이를 이해할 때 발생합니다. 즉, 새로운 패러다임의 선택은 그것들 관찰이 기존 패러다임을 배경에 대항하여 이루어지더라도 관찰을 기반으로 합니다. 쿤에게 있어, 패러다임의 수용과 거부는 논리적인 과정인 동시에 사회적인 과정입니다. Kuhn의 입장은, 어쨌든, 상대주의(elativism) 중의 하나가 아닙니다.[202]

마지막으로, "창조 과학(creation science)"과 같은 논쟁의 여지가 있는 운동에 대한 과학적 회의론(scientific skepticism)의 논쟁에서 자주 인용되는 또 다른 접근법은 방법론적 자연주의(methodological naturalism)입니다. 자연주의자들은 자연과 초자연 사이에 차이가 있어야 하고, 과학은 자연적 설명으로 제한되어야 한다고 주장합니다.[203] 방법론적 자연주의는 과학이 경험적(empirical) 연구와 독립적인 검증에 대한 엄격한 준수를 요구한다고 주장합니다.[204]

Scientific community

과학 공동체(scientific community)는 과학 연구를 수행하는 상호 작용하는 과학자의 네트워크입니다. 공동체는 과학 분야에서 일하는 더 작은 그룹으로 구성됩니다. 동료 검토(peer review)를 가짐으로써, 학술지와 학회 내 토론과 논쟁을 통해 과학자들은 결과를 해석할 때 연구 방법론의 품질과 객관성을 유지합니다.[205]

Scientists

과학자(Scientists)는 관심 분야의 지식을 발전시키기 위해 과학적 연구를 수행하는 개인입니다.[206][207] 현대에는, 많은 전문 과학자들이 학문적 환경에서 훈련을 받고 수료 후 학사 학위(academic degree)를 취득하며, 가장 높은 학위는 박사 학위(Doctor of Philosophy 또는 PhD)와 같은 박사호(doctorate)입니다.[208] 많은 과학자들이 학계, 산업체, 정부, 및 비영리 단체와 같은 경제의 다양한 부문에서 경력을 추구합니다.[209][210][211]

과학자들은 현실(reality)에 대한 강한 호기심과 건강, 국가, 환경, 또는 산업의 이익을 위해 과학적 지식을 적용하려는 열망을 나타냅니다. 다른 동기에는 동료의 인정과 명성을 포함합니다. 현대에는 많은 과학자들이 과학 분야에서 학위를 취득했고[212] 학계, 산업, 정부, 및 비영리 환경과 같은 경제의 다양한 분야에서 경력을 추구합니다.[213][214]

과학은 역사적으로 주목할만한 예외를 제외하고는 남성이 지배하는 분야였습니다. 과학계의 여성은 남성이 지배하는 사회의 다른 영역에서와 마찬가지로 과학에서 상당한 차별에 직면했습니다. 예를 들어, 여성은 종종 취업 기회를 놓치고 그들 연구에 대한 공인을 거부당했습니다.[215] 과학 분야에서 여성의 업적은 가사 영역(domestic sphere) 내에서 노동자로서의 전통적인 역할에 대한 도전에 기인합니다.[216] 라이프스타일 선택은 여성의 과학 참여에 중요한 역할을 합니다; 연구 경력에 대한 여성 대학원생의 관심은 대학원 전반에 걸쳐 급격히 감소하는 반면 남성 동료의 관심은 변함이 없습니다.[217]

Learned societies

과학적 사고와 실험의 의사소통과 촉진을 위한 학식 있는 사회(Learned societies)는 르네상스 이후에 존재해 왔습니다.[218] 많은 과학자들은 각자의 과학 분야, 직업(profession), 또는 관련 분야 그룹을 장려하는 학식 있는 사회에 속해 있습니다.[219] 회원 자격은 모든 사람에게 공개되거나, 과학적 자격 증명을 요구하거나, 선거에 의해 부여될 수 있습니다.[220] 대부분의 과학 협회는 비영리 조직(non-profit organizations)이고, 많은 경우 전문 협회(professional associations)입니다. 그들의 활동에는 전형적으로 새로운 연구 결과의 발표와 토론을 위한 정기 학회(conferences) 개최와 해당 분야의 학술지(academic journals) 출판 또는 후원을 포함합니다. 일부 협회는 공익 또는 회원 집단의 이익을 위해 회원의 활동을 규제하는 전문 기관(professional bodies)의 역할을 합니다.

19세기에 시작된 과학의 전문화는 1603년 이탈리아 Accademia dei Lincei,[221] 1660년 영국 Royal Society,[222] 1666년 French Academy of Sciences,[223] 1863년 미국 National Academy of Sciences,[224] 1911년 독일 Kaiser Wilhelm Society,[225] 및 1949년 Chinese Academy of Sciences과[226] 같은 국립 과학 아카데미(academies of sciences)의 설립으로 부분적으로 가능했습니다. 국제 과학 위원회(International Science Council)와 같은 국제 과학 기구는 과학 발전을 위한 국제 협력에 전념하고 있습니다.[227]

Awards

과학상(Science awards)은 보통 학문 분야에 상당한 공헌을 한 개인이나 조직에 수여됩니다. 그들은 권위 있는 기관에서 주는 경우가 많기 때문에 이를 받는 과학자에게 큰 영예를 안겨줍니다. 초기 르네상스 이후, 과학자들은 종종 메달, 상금, 및 칭호를 받았습니다. 널리 알려진 권위 있는 상, 노벨상(Nobel Prize)은 의학(medicine), 물리학(physics), 및 화학(chemistry) 분야에서 과학적 발전을 이룬 사람들에게 매년 수여됩니다.[228]

Society

Funding and policies

과학 연구는 종종 잠재적인 연구 프로젝트가 평가되고 가장 유망한 경우에만 자금이 지원되는 경쟁 과정을 통해 자금이 지원됩니다. 정부, 기업, 또는 재단에 의해 운영되는 그러한 프로세스는 부족한 자금을 할당합니다. 대부분의 선진국(developed countries)에서 총 연구 자금은 GDP의 1.5%에서 3% 사이입니다.[229] OECD에서, 과학과 기술 분야에서 연구와 개발(research and development)의 약 3분의 2가 산업체에 의해 수행되고, 대학교와 정부에 의해 각각 20%와 10%가 수행됩니다. 특정 분야에서 정부 지원 비율이 더 높고, 그것이 사회 과학과 인문학(humanities) 연구를 지배합니다. 저-개발 국가에서, 정부가 기초 과학 연구를 위한 기금의 대부분을 제공합니다.[230]

미국에서 National Science Foundation,[231] 아르헨티나에서 National Scientific and Technical Research Council,[232] 호주에서 Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization,[233] 프랑스에서 National Centre for Scientific Research,[234] 독일에서 Max Planck Society,[235] 및 스페인에서 National Research Council와[236] 같은 많은 정부는 과학 연구를 지원하기 위해 전담 기관을 보유하고 있습니다. 상업적 연구와 개발에서, 가장 연구 지향적인 기업을 제외한 모든 기업은 호기심에 의한 연구보다 단기 상업화 가능성에 더 중점을 둡니다.[237]

과학 정책(Science policy)은 상업 제품 개발, 무기 개발, 건강 관리, 및 환경 모니터링을 촉진하기 위한 기술 혁신과 같은 다른 국가 정책 목표를 추구하는 연구 자금 지원(research funding)을 포함하여 과학 기업의 수행에 영향을 미치는 정책과 관련이 있습니다. 과학 정책은 때때로 공공 정책 개발에 과학적 지식과 합의를 적용하는 행위를 말합니다. 시민의 복지에 관심을 갖는 공공 정책에 따라, 과학 정책의 목표는 과학과 기술이 대중에게 가장 잘 봉사할 수 있는 방법을 고려하는 것입니다.[238] 공공 정책은 연구 자금을 지원하는 조직에 세금 인센티브를 제공함으로써 산업 연구를 위한 자본 장비(capital equipment)와 지적 기반 시설의 자금 조달에 직접적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[184]

Education and awareness

일반 대중을 위한 과학 교육(Science education)은 과학 콘텐츠, 과학적 방법, 및 일부 교육학(pedagogy)에서 연구를 포함합니다. 학생이 정규 교육(formal education)의 상위 단계로 발전함에 따라, 교육 과정(curriculum)은 더욱 심화됩니다. 최근의 움직임에는 사회와 응용 과학도 포함되지만, 보통 교육 과정에 포함되는 전통적인 과목은 자연과 형식 과학입니다.[239]

대중 매체(mass media)는 전체로 과학 공동체 내에서 그들의 신뢰성 측면에서 경쟁적인 과학적 주장을 정확하게 묘사하는 것을 방해할 수 있는 압력에 직면해 있습니다. 과학적 논쟁(scientific debate)에서 서로 다른 편에 얼마나 많은 비중을 둘 것인지를 결정하는 것은 그 문제에 대한 상당한 전문 지식을 요구할 수 있습니다.[240] 진정한 과학적 지식을 가진 언론인은 거의 없고, 심지어 특정 과학적 문제에 대해 잘 알고 있는 전문 기자(beat reporters)조차 갑자기 취재를 요청받은 다른 과학적 문제에 대해서는 무지할 수 있습니다.[241][242]

New Scientist, Science & Vie, 및 Scientific American와 같은 과학 잡지는 훨씬 더 넓은 독자층의 요구를 충족하고 특정 연구 분야의 주목할만한 발견과 발전을 포함하여 인기 있는 연구 분야에 대한 비기술적 요약을 제공합니다.[243] 주로 사변적 소설(speculative fiction), 공상 과학 소설(Science fiction) 장르는 과학의 아이디어와 방법을 일반 대중에게 전달할 수 있습니다.[244] 과학과 문학이나 시와 같은 비과학 분야 사이의 연결을 강화하거나 발전시키려는 최근의 노력에는 Royal Literary Fund를 통해 개발된 Creative Writing Science 자원을 포함합니다.[245]

Anti-science attitudes

과학적 방법은 과학 공동체에서 널리 받아들여지고 있지만, 사회의 많은 부분이 많은 과학적 입장을 거부하거나 과학에 대해 회의적입니다. 예를 들면 COVID-19가 주요 건강 위협이 아니라는 일반적인 개념 (2021년 9월 미국인의 약 40%가 생각함)[246] 또는 기후 변화가 주요 위협이 아니라는 믿음 (미국인의 40%, 2020년 4월)이 있습니다.[247] 심리학자들(Psychologists)은 과학적 결과를 거부하는 네 가지 요인을 지적했습니다:[248]

- 과학 권위자는 때때로 비전문가, 신뢰할 수 없거나, 편향된 것으로 보입니다.

- 일부 소외된 사회 집단은 부분적으로는 비윤리적 실험에서 종종 이용되기 때문에 반과학적인 태도를 취합니다.[249]

- 과학자들로부터 메시지는 깊이 간직되어 있는 기존 신념이나 도덕(morals)과 모순될 수 있습니다.

- 과학적 메시지의 전달(delivery)은 수신자의 학습 스타일에 적절한 목표가 아닐 수 있습니다.

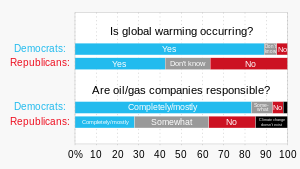

반-과학적 태도는 종종 사회 집단에서 거부당하는 것에 대한 두려움으로 인해 발생하는 것 같습니다. 예를 들어, 기후 변화는 정치적 스펙트럼의 오른쪽에 있는 미국인의 22%만이 위협으로 인식하지만, 왼쪽에 있는 미국인의 85%는 위협으로 인식합니다.[250] 즉, 좌파의 누군가가 기후변화를 위협으로 여기지 않는다면, 이 사람은 모욕을 당하고 그 사회 집단에서 거부당할 수 있습니다. 사실, 사람들은 사회적 지위를 잃거나 위태롭게 하기보다는 과학적으로 받아들여진 사실을 부정하는 편이 낫습니다.[251]

Politics

과학을 향한 태도는 종종 정치적 견해와 목표에 의해 결정됩니다. 정부, 기업, 및 옹호 단체는 과학 연구자들에게 영향을 미치기 위해 법적, 경제적 압력을 사용하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다. 반-지성주의(anti-intellectualism), 종교적 신념에 대한 위협 인식, 및 비즈니스 이익에 대한 두려움과 같은 많은 요인이 과학 정치화(politicization of science)의 측면으로 작용할 수 있습니다.[253] 과학의 정치화는 보통 과학적 증거와 관련된 불확실성을 강조하는 방식으로 과학적 정보가 제시될 때 달성됩니다.[254] 대화를 전환하고, 사실을 인정하지 않고, 과학적 합의(scientific consensus)에 대한 의심을 이용하는 것과 같은 전술은 과학적 증거에 의해 훼손된 견해에 대해 더 많은 관심을 끌기 위해 사용되어 왔습니다.[255] 과학의 정치화와 관련된 문제의 예로는 지구 온난화 논쟁(global warming controversy), 살충제의 건강 영향(health effects of pesticides), 및 담배의 건강 영향(health effects of tobacco)을 포함합니다.[255][256]

See also

- Anti-science

- Index of branches of science

- List of scientific occupations

- List of years in science

- Outline of science

Notes

- ^ Whether the universe is closed or open, or the shape of the universe, is an open question. The 2nd law of thermodynamics,[110]: 9 [111]: 158 and the 3rd law of thermodynamics[112]: 665–681 imply the heat death of the universe if the universe is a closed system, but not necessarily for an expanding universe.

References

- ^ Wilson, E.O. (1999). "The natural sciences". Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (Reprint ed.). New York: Vintage. pp. 49–71. ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8.

- ^ Heilbron, J.L.; et al. (2003). "Preface". The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–x. ISBN 978-0-19-511229-0.

...modern science is a discovery as well as an invention. It was a discovery that nature generally acts regularly enough to be described by laws and even by mathematics; and required invention to devise the techniques, abstractions, apparatus, and organization for exhibiting the regularities and securing their law-like descriptions.

- ^ Liebenberg, Louis (2021). The Origin of Science (2 ed.). p. 4.

- ^ a b Liebenberg, Louis; //Ao, /Am; Lombard, Marlize; Shermer, Michael; Xhukwe, /Uase; Biesele, Megan; //Xao, Di; Carruthers, Peter; Kxao, ≠Oma; Hansson, Sven Ove; Langwane, Horekhwe (Karoha); Elbroch, L. Mark; /Ui, N≠Aisa; Keeping, Derek; Humphrey, Glynis; Newman, Greg; g/Aq'o, /Ui; Steventon, Justin; Kashe, Njoxlau; Stevenson, Robert; Benadie, Karel; Du Plessis, Pierre; Minye, James; /Kxunta, /Ui; Ludwig, Bettina; Daqm, ≠Oma; Louw, Marike; Debe, Dam; Voysey, Michael (2021). "Tracking Science: An Alternative for Those Excluded by Citizen Science". Citizen Science: Theory and Practice. 6. doi:10.5334/cstp.284. S2CID 233291257.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e "The historian ... requires a very broad definition of "science" – one that ... will help us to understand the modern scientific enterprise. We need to be broad and inclusive, rather than narrow and exclusive ... and we should expect that the farther back we go [in time] the broader we will need to be." p.3—Lindberg, David C. (2007). "Science before the Greeks". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ a b Grant, Edward (2007). "Ancient Egypt to Plato". A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (First ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-521-68957-1.

- ^ a b c d Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The revival of learning in the West". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 193–224. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "Islamic science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 163–92. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The recovery and assimilation of Greek and Islamic science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 225–53. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Principe, Lawrence M. (2011). "Introduction". Scientific Revolution: A Very Short Introduction (First ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-19-956741-6.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The legacy of ancient and medieval science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 357–368. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Grant, Edward (2007). "Transformation of medieval natural philosophy from the early period modern period to the end of the nineteenth century". A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (First ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 274–322. ISBN 978-0-521-68957-1.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (2015). The Territories of Science and Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-226-18451-7.

The changing character of those engaged in scientific endeavors was matched by a new nomenclature for their endeavors. The most conspicuous marker of this change was the replacement of "natural philosophy" by "natural science". In 1800 few had spoken of the "natural sciences" but by 1880, this expression had overtaken the traditional label "natural philosophy". The persistence of "natural philosophy" in the twentieth century is owing largely to historical references to a past practice (see figure 11). As should now be apparent, this was not simply the substitution of one term by another, but involved the jettisoning of a range of personal qualities relating to the conduct of philosophy and the living of the philosophical life.

- ^ Cahan, David, ed. (2003). From Natural Philosophy to the Sciences: Writing the History of Nineteenth-Century Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-08928-7.

- ^ Lightman, Bernard (2011). "13. Science and the Public". In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter (eds.). Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- ^ a b Cohen, Eliel (2021). "The boundary lens: theorising academic actitity". The University and its Boundaries: Thriving or Surviving in the 21st Century 1st Edition. New York: Routledge. pp. 14–41. ISBN 978-0-367-56298-4. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Colander, David C.; Hunt, Elgin F. (2019). "Social science and its methods". Social Science: An Introduction to the Study of Society (17th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 1–22.

- ^ a b Nisbet, Robert A.; Greenfeld, Liah (October 16, 2020). "Social Science". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on February 2, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Löwe, Benedikt (2002). "The formal sciences: their scope, their foundations, and their unity". Synthese. 133 (1/2): 5–11. doi:10.1023/A:1020887832028. S2CID 9272212.

- ^ a b Rucker, Rudy (2019). "Robots and souls". Infinity and the Mind: The Science and Philosophy of the Infinite (Reprint ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 157–188. ISBN 978-0-691-19138-6. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Bishop, Alan (1991). "Environmental activities and mathematical culture". Mathematical Enculturation: A Cultural Perspective on Mathematics Education. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 20–59. ISBN 978-0-7923-1270-3. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ a b Nickles, Thomas (2013). "The Problem of Demarcation". Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 104.

- ^ Bunge, Mario (1998). "The Scientific Approach". Philosophy of Science. Vol. 1, From Problem to Theory (revised ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 3–50. ISBN 978-0-7658-0413-6.

- ^ a b Fetzer, James H. (2013). "Computer reliability and public policy: Limits of knowledge of computer-based systems". Computers and Cognition: Why Minds are not Machines. Newcastle, United Kingdom: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 271–308. ISBN 978-1-4438-1946-6.

- ^ Fischer, M.R.; Fabry, G (2014). "Thinking and acting scientifically: Indispensable basis of medical education". GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbildung. 31 (2): Doc24. doi:10.3205/zma000916. PMC 4027809. PMID 24872859.

- ^ Sinclair, Marius (1993). "On the Differences between the Engineering and Scientific Methods". The International Journal of Engineering Education. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Bunge, M (1966). "Technology as applied science". In Rapp, F. (ed.). Contributions to a Philosophy of Technology. Theory and Decision Library (An International Series in the Philosophy and Methodology of the Social and Behavioral Sciences). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. pp. 19–39. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-2182-1_2. ISBN 978-94-010-2184-5.

- ^ MacRitchie, Finlay (2011). "Introduction". Scientific Research as a Career. New York: Routledge. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-1-4398-6965-9. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Marder, Michael P. (2011). "Curiosity and research". Research Methods for Science. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-0-521-14584-8. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ de Ridder, Jeroen (2020). "How many scientists does it take to have knowledge?". In McCain, Kevin; Kampourakis, Kostas (eds.). What is Scientific Knowledge? An Introduction to Contemporary Epistemology of Science. New York: Routledge. pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-1-138-57016-0. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "Islamic science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 163–192. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Szycher, Michael (2016). "Establishing your dream team". Commercialization Secrets for Scientists and Engineers. New York: Routledge. pp. 159–176. ISBN 978-1-138-40741-1. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ "science". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ Vaan, Michiel de (2008). "sciō". Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the other Italic Languages. Indo-European Etymological Dictionary. p. 545. ISBN 978-90-04-16797-1.

- ^ Cahan, David (2003). From natural philosophy to the sciences : writing the history of nineteenth-century science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-08927-4. OCLC 51330464. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Ross, Sydney (1962). "Scientist: The story of a word". Annals of Science. 18 (2): 65–85. doi:10.1080/00033796200202722.

- ^ Budd, Paul; Taylor, Timothy (1995). "The Faerie Smith Meets the Bronze Industry: Magic Versus Science in the Interpretation of Prehistoric Metal-Making". World Archaeology. 27 (1): 133–143. doi:10.1080/00438243.1995.9980297. JSTOR 124782.

- ^ Graeber, David; Wengrow, David (2021). The Dawn of Everything. p. 248.

- ^ Scott, Colin (2011). "Science for the West, Myth for the Rest?". In Harding, Sandra (ed.). The Postcolonial Science and Technology Studies Reader. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 175. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11g96cc.16. ISBN 978-0-8223-4936-5. OCLC 700406626.

- ^ Rochberg, Francesca (2011). "Ch.1 Natural Knowledge in Ancient Mesopotamia". In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter (eds.). Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- ^ Krebs, Robert E. (2004). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 127. ISBN 978-0313324338.

- ^ Erlich, Ḥaggai; Gershoni, Israel (2000). The Nile: Histories, Cultures, Myths. Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-1-55587-672-2. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

The Nile occupied an important position in Egyptian culture; it influenced the development of mathematics, geography, and the calendar; Egyptian geometry advanced due to the practice of land measurement "because the overflow of the Nile caused the boundary of each person's land to disappear."

- ^ "Telling Time in Ancient Egypt". www.metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c McIntosh, Jane R. (2005). Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, California, Denver, Colorado, and Oxford, England: ABC-CLIO. pp. 273–76. ISBN 978-1-57607-966-9. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Aaboe, Asger (May 2, 1974). "Scientific Astronomy in Antiquity". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 276 (1257): 21–42. Bibcode:1974RSPTA.276...21A. doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0007. JSTOR 74272. S2CID 122508567.

- ^ Biggs, R D. (2005). "Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health in Ancient Mesopotamia". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 19 (1): 7–18.

- ^ Lehoux, Daryn (2011). "2. Natural Knowledge in the Classical World". In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter (eds.). Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- ^ An account of the pre-Socratic use of the concept of φύσις may be found in Naddaf, Gerard (2006) The Greek Concept of Nature, SUNY Press, and in Ducarme, Frédéric; Couvet, Denis (2020). "What does 'nature' mean?". Palgrave Communications. 6 (14). Springer Nature. doi:10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y.. The word φύσις, while first used in connection with a plant in Homer, occurs early in Greek philosophy, and in several senses. Generally, these senses match rather well the current senses in which the English word nature is used, as confirmed by Guthrie, W.K.C. Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus (volume 2 of his History of Greek Philosophy), Cambridge UP, 1965.

- ^ Strauss, Leo; Gildin, Hilail (1989). "Progress or Return? The Contemporary Crisis in Western Education". An Introduction to Political Philosophy: Ten Essays by Leo Strauss. Wayne State University Press (published August 1, 1989). ISBN 978-0814319024. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ O'Grady, Patricia F. (2016). Thales of Miletus: The Beginnings of Western Science and Philosophy. New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-7546-0533-1. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Burkert, Walter (June 1, 1972). Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-53918-1. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018.

- ^ Pullman, Bernard (1998). The Atom in the History of Human Thought. pp. 31–33. Bibcode:1998ahht.book.....P. ISBN 978-0-19-515040-7. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Cohen, Henri; Lefebvre, Claire, eds. (2017). Handbook of Categorization in Cognitive Science (Second ed.). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. p. 427. ISBN 978-0-08-101107-2. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Margotta, Roberto (1968). The Story of Medicine. New York City, New York: Golden Press. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Touwaide, Alain (2005). Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven; Wallis, Faith (eds.). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-415-96930-7. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Leff, Samuel; Leff, Vera (1956). From Witchcraft to World Health. London, England: Macmillan. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ "Plato, Apology". p. 17. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ^ "Plato, Apology". p. 27. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ^ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics (H. Rackham ed.). Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2010. 1139b

- ^ a b McClellan III, James E.; Dorn, Harold (2015). Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-4214-1776-9. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Graßhoff, Gerd (1990). The History of Ptolemy's Star Catalogue. Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. Vol. 14. New York, NY: Springer New York. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4468-4. ISBN 978-1-4612-8788-9. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Hoffmann, Susanne M. (2017). Hipparchs Himmelsglobus (in German). Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. Bibcode:2017hihi.book.....H. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-18683-8. ISBN 978-3-658-18682-1. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Edwards, C.H. Jr. (1979). The Historical Development of the Calculus (First ed.). New York City, New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-387-94313-8. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Lawson, Russell M. (2004). Science in the Ancient World: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 190–91. ISBN 978-1-85109-539-1. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Murphy, Trevor Morgan (2004). Pliny the Elder's Natural History: The Empire in the Encyclopedia. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-926288-5. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Doody, Aude (2010). Pliny's Encyclopedia: The Reception of the Natural History. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-139-48453-4. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c Lindberg, David C. (2007). "Roman and early medieval science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 132–162. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Grant, Edward (1996). The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional and Intellectual Contexts. Cambridge Studies in the History of Science. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–17. ISBN 978-0-521-56762-6. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- ^ Wildberg, Christian (May 1, 2018). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2018 – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Falcon, Andrea (2019). "Aristotle on Causality". In Zalta, Edward (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Grant, Edward (2007). "Islam and the eastward shift of Aristotelian natural philosophy". A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–67. ISBN 978-0-521-68957-1.

- ^ Fisher, W.B. (William Bayne) (1968–1991). The Cambridge history of Iran. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6. OCLC 745412.

- ^ "Bayt al-Hikmah". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ Hossein Nasr, Seyyed; Leaman, Oliver, eds. (2001). History of Islamic Philosophy. Routledge. pp. 165–167. ISBN 9780415259347.

- ^ Toomer, G.J. (1964). "Reviewed work: Ibn al-Haythams Weg zur Physik, Matthias Schramm". Isis. 55 (4): 463–65. doi:10.1086/349914. JSTOR 228328. See p. 464: "Schramm sums up [Ibn Al-Haytham's] achievement in the development of scientific method.", p. 465: "Schramm has demonstrated .. beyond any dispute that Ibn al-Haytham is a major figure in the Islamic scientific tradition, particularly in the creation of experimental techniques." p. 465: "only when the influence of ibn al-Haytam and others on the mainstream of later medieval physical writings has been seriously investigated can Schramm's claim that ibn al-Haytam was the true founder of modern physics be evaluated."

- ^ Cohen, H. Floris (2010). "Greek nature knowledge transplanted: The Islamic world". How modern science came into the world. Four civilizations, one 17th-century breakthrough (Second ed.). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 99–156. ISBN 978-90-8964-239-4.

- ^ a b Smith, A. Mark (2001). Alhacen's Theory of Visual Perception: A Critical Edition, with English Translation and Commentary, of the First Three Books of Alhacen's De Aspectibus, the Medieval Latin Version of Ibn al-Haytham's Kitāb al-Manāẓir, 2 vols. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 91. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-914-5. OCLC 47168716.

- ^ Selin, Helaine, ed. (2006). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. pp. 155–156. Bibcode:2008ehst.book.....S. ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- ^ Russell, Josiah C. (1959). "Gratian, Irnerius, and the Early Schools of Bologna". The Mississippi Quarterly. 12 (4): 168–188. JSTOR 26473232. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022 – via JSTOR.

Perhaps even as early as 1088 (the date officially set for the founding of the University)

- ^ "St. Albertus Magnus | German theologian, scientist, and philosopher". Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Numbers, Ronald (2009). Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion. Harvard University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-674-03327-6. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Smith, A. Mark (1981). "Getting the Big Picture in Perspectivist Optics". Isis. 72 (4): 568–89. doi:10.1086/352843. JSTOR 231249. PMID 7040292. S2CID 27806323.

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R (2016). "Copernicus and the Origin of his Heliocentric System" (PDF). Journal for the History of Astronomy. 33 (3): 219–35. doi:10.1177/002182860203300301. S2CID 118351058. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ Cohen, H. Floris (2010). "Greek nature knowledge transplanted and more: Renaissance Europe". How modern science came into the world. Four civilizations, one 17th-century breakthrough (Second ed.). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 99–156. ISBN 978-90-8964-239-4.

- ^ Koestler, Arthur (1990) [1959]. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. London: Penguin Books. p. 1. ISBN 0-14-019246-8.

- ^ van Helden, Al (1995). "Pope Urban VIII". The Galileo Project. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ Owen Gingerich, "Copernicus and the Impact of Printing." Vistas in Astronomy 17 (1975): 201-218.

- ^ Zagorin, Perez (1998), Francis Bacon, Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 84, ISBN 978-0-691-00966-7

- ^ Davis, Philip J., and Reuben Hersh. 1986. Descartes' Dream: The World According to Mathematics. Cambridge, MA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- ^ "Although it was just one of the many factors in the Enlightenment, the success of Newtonian physics in providing a mathematical description of an ordered world clearly played a big part in the flowering of this movement in the eighteenth century" by John Gribbin, Science: A History 1543–2001 (2002), p. 241 ISBN 978-0-7139-9503-9

- ^ "Gottfried Leibniz – Biography". Maths History. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ Freudenthal, Gideon; McLaughlin, Peter (May 20, 2009). The Social and Economic Roots of the Scientific Revolution: Texts by Boris Hessen and Henryk Grossmann. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-9604-4. Archived from the original on January 19, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ Goddard Bergin, Thomas; Speake, Jennifer, eds. (1987). Encyclopedia of the Renaissance. Facts on File (published December 1, 1987). ISBN 978-0816013159.

- ^ van Horn Melton, James (2001). The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511819421. ISBN 9780511819421. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Cassels, Alan (1996). Ideology and International Relations in the Modern World. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 9781134813308. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Madigan M, Martinko J, eds. (2006). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0131443297.

- ^ Guicciardini, N. (1999). Reading the Principia: The Debate on Newton's Methods for Natural Philosophy from 1687 to 1736. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521640664.

- ^ Calisher, CH (2007). "Taxonomy: what's in a name? Doesn't a rose by any other name smell as sweet?". Croatian Medical Journal. 48 (2): 268–270. PMC 2080517. PMID 17436393.

- ^ Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198505949.

- ^ Olby, R.C., G.N Cantor, J.R.R. Christie, and M.J.S. Hodge. 1990. ''Companion to the History of Modern Science''. London: Routledge

- ^ Magnusson, Magnus (November 10, 2003). "Review of James Buchan, Capital of the Mind: how Edinburgh Changed the World". New Statesman. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ Swingewood, Alan (1970). "Origins of Sociology: The Case of the Scottish Enlightenment". The British Journal of Sociology. 21 (2): 164–180. doi:10.2307/588406. JSTOR 588406.

- ^ Fry, Michael (1992). Adam Smith's Legacy: His Place in the Development of Modern Economics. Paul Samuelson, Lawrence Klein, Franco Modigliani, James M. Buchanan, Maurice Allais, Theodore Schultz, Richard Stone, James Tobin, Wassily Leontief, Jan Tinbergen. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06164-3.

- ^ Lightman, Bernard (2011). "13. Science and the Public". In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter (eds.). Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- ^ Leahey, Thomas Hardy (2018). "The psychology of consciousness". A History of Psychology: From Antiquity to Modernity (8th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 219–253. ISBN 978-1-138-65242-2.

- ^ Padian, Kevin (2008). "Darwin's enduring legacy". Nature. 451 (7179): 632–634. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..632P. doi:10.1038/451632a. PMID 18256649.

- ^ Henig, Robin Marantz (2000). The monk in the garden: the lost and found genius of Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics. pp. 134–138.

- ^ Miko, Ilona (2008). "Gregor Mendel's principles of inheritance form the cornerstone of modern genetics. So just what are they?". Nature Education. 1 (1): 134. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ Rocke, Alan J. (2005). "In Search of El Dorado: John Dalton and the Origins of the Atomic Theory". Social Research. 72 (1): 125–158. doi:10.1353/sor.2005.0003. JSTOR 40972005.

- ^ a b Reichl, Linda (1980). A Modern Course in Statistical Physics. Edward Arnold. ISBN 0-7131-2789-9.

- ^ Rao, Y. V. C. (1997). Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics. Universities Press. ISBN 978-81-7371-048-3.

- ^ Heidrich, M. (2016). "Bounded energy exchange as an alternative to the third law of thermodynamics". Annals of Physics. 373: 665–681. Bibcode:2016AnPhy.373..665H. doi:10.1016/j.aop.2016.07.031. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ Mould, Richard F. (1995). A century of X-rays and radioactivity in medicine: with emphasis on photographic records of the early years (Reprint. with minor corr ed.). Bristol: Inst. of Physics Publ. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7503-0224-1.

- ^ a b Estreicher, Tadeusz (1938). "Curie, Maria ze Skłodowskich". Polski słownik biograficzny, vol. 4 (in Polish). p. 113.

- ^ Thomson, J.J. (1897). "Cathode Rays". Philosophical Magazine. 44 (269): 293–316. doi:10.1080/14786449708621070. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ Goyotte, Dolores (2017). "The Surgical Legacy of World War II. Part II: The age of antibiotics" (PDF). The Surgical Technologist. 109: 257–264. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Erisman, Jan Willem; MA Sutton; J Galloway; Z Klimont; W Winiwarter (October 2008). "How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world". Nature Geoscience. 1 (10): 636–639. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1..636E. doi:10.1038/ngeo325. S2CID 94880859. Archived from the original on July 23, 2010. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Emmett, Rob, and Frank Zelko (eds.), "Minding the Gap: Working Across Disciplines in Environmental Studies Archived January 21, 2022, at the Wayback Machine," RCC Perspectives 2014, no. 2. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/6313

- ^ Furner, Jonathan (June 1, 2003). "Little Book, Big Book: Before and After Little Science, Big Science: A Review Article, Part I". Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. 35 (2): 115–125. doi:10.1177/0961000603352006. S2CID 34844169.

- ^ Kraft, Chris; James Schefter (2001). Flight: My Life in Mission Control. New York: Dutton. ISBN 0-525-94571-7.

- ^ Herman Kahn (1962) Thinking about the Unthinkable, Horizon Press.

- ^ Shrum, Wesley (2007). Structures of scientific collaboration. Joel Genuth, Ivan Chompalov. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-28358-8. OCLC 166143348. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Rosser, Sue V. (March 12, 2012). Breaking into the Lab: Engineering Progress for Women in Science. New York: New York University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8147-7645-2.

- ^ Penzias, A. A. (2006). "The origin of elements" (PDF). Science. 205 (4406). Nobel Foundation: 549–54. doi:10.1126/science.205.4406.549. PMID 17729659. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2006.

- ^ Weinberg, S. (1972). Gravitation and Cosmology. John Whitney & Sons. pp. 495–464. ISBN 978-0-471-92567-5.

- ^ Futuyma, Douglas J.; Kirkpatrick, Mark (April 2017). "Chapter 1: Evolutionary Biology". Evolution (4th ed.). pp. 3–26. ISBN 9781605356051. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Arthur I. (1981), Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity. Emergence (1905) and early interpretation (1905–1911), Reading: Addison–Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-04679-3

- ^ ter Haar, D. (1967). The Old Quantum Theory. Pergamon Press. pp. 206. ISBN 978-0-08-012101-7.

- ^ von Bertalanffy, Ludwig (1972). "The History and Status of General Systems Theory". The Academy of Management Journal. 15 (4): 407–26. doi:10.2307/255139. JSTOR 255139.

- ^ Naidoo, Nasheen; Pawitan, Yudi; Soong, Richie; Cooper, David N.; Ku, Chee-Seng (October 2011). "Human genetics and genomics a decade after the release of the draft sequence of the human genome". Human Genomics. 5 (6): 577–622. doi:10.1186/1479-7364-5-6-577. PMC 3525251. PMID 22155605.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Rashid, S. Tamir; Alexander, Graeme J.M. (March 2013). "Induced pluripotent stem cells: from Nobel Prizes to clinical applications". Journal of Hepatology. 58 (3): 625–629. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.026. ISSN 1600-0641. PMID 23131523.

- ^ O'Luanaigh, C. (March 14, 2013). "New results indicate that new particle is a Higgs boson" (Press release). CERN. Archived from the original on October 20, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; Adya, V.B.; Affeldt, C.; Afrough, M.; Agarwal, B.; Agathos, M.; Agatsuma, K.; Aggarwal, N.; Aguiar, O.D.; Aiello, L.; Ain, A.; Ajith, P.; Allen, B.; Allen, G.; Allocca, A.; Altin, P.A.; Amato, A.; Ananyeva, A.; Anderson, S.B.; Anderson, W.G.; Angelova, S.V.; et al. (2017). "Multi-messenger Observations of a Binary Neutron Star Merger". The Astrophysical Journal. 848 (2): L12. arXiv:1710.05833. Bibcode:2017ApJ...848L..12A. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa91c9. S2CID 217162243.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Cho, Adrian (2017). "Merging neutron stars generate gravitational waves and a celestial light show". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aar2149.

- ^ "Media Advisory: First Results from the Event Horizon Telescope to be Presented on April 10th | Event Horizon Telescope". April 20, 2019. Archived from the original on April 20, 2019. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ "Scientific Method: Relationships Among Scientific Paradigms". Seed Magazine. March 7, 2007. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ^ Bunge, Mario Augusto (1998). Philosophy of Science: From Problem to Theory. Transaction Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7658-0413-6.

- ^ a b Popper, Karl R. (2002a) [1959]. "A survey of some fundamental problems". The Logic of Scientific Discovery. New York: Routledge Classics. pp. 3–26. ISBN 978-0-415-27844-7. OCLC 59377149.

- ^ Gauch Jr., Hugh G. (2003). "Science in perspective". Scientific Method in Practice. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–73. ISBN 978-0-521-01708-4. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ Oglivie, Brian W. (2008). "Introduction". The Science of Describing: Natural History in Renaissance Europe (Paperback ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-0-226-62088-6.

- ^ "Natural History". Princeton University WordNet. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ "Formal Sciences: Washington and Lee University". Washington and Lee University. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

A "formal science" is an area of study that uses formal systems to generate knowledge such as in Mathematics and Computer Science. Formal sciences are important subjects because all of quantitative science depends on them.

- ^ "formal system". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on April 29, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Tomalin, Marcus (2006). Linguistics and the Formal Sciences.

- ^ Löwe, Benedikt (2002). "The Formal Sciences: Their Scope, Their Foundations, and Their Unity". Synthese. 133: 5–11. doi:10.1023/a:1020887832028. S2CID 9272212.

- ^ Bill, Thompson (2007). "2.4 Formal Science and Applied Mathematics". The Nature of Statistical Evidence. Lecture Notes in Statistics. Vol. 189. Springer. p. 15.

- ^ Bunge, Mario (1998). "The Scientific Approach". Philosophy of Science: Volume 1, From Problem to Theory. Vol. 1 (revised ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 3–50. ISBN 978-0-7658-0413-6.

- ^ Mujumdar, Anshu Gupta; Singh, Tejinder (2016). "Cognitive science and the connection between physics and mathematics". In Aguirre, Anthony; Foster, Brendan (eds.). Trick or Truth?: The Mysterious Connection Between Physics and Mathematics. The Frontiers Collection (1st ed.). Switzerland: SpringerNature. pp. 201–218. ISBN 978-3-319-27494-2.

- ^ "About the Journal". Journal of Mathematical Physics. Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved October 3, 2006.

- ^ Restrepo, G. Mathematical chemistry, a new discipline. In Essays in the philosophy of chemistry, Scerri, E.; Fisher, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, UK, 2016; Chapter 15, 332-351. [1] Archived June 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "What is mathematical biology | Centre for Mathematical Biology | University of Bath". www.bath.ac.uk. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Tim (September 1, 2009). "What is financial mathematics?". +Plus Magazine. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ Varian, Hal (1997). "What Use Is Economic Theory?" in A. D'Autume and J. Cartelier, ed., Is Economics Becoming a Hard Science?, Edward Elgar. Pre-publication PDF. Archived June 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- ^ Abraham, Reem Rachel (2004). "Clinically oriented physiology teaching: strategy for developing critical-thinking skills in undergraduate medical students". Advances in Physiology Education. 28 (3): 102–04. doi:10.1152/advan.00001.2004. PMID 15319191. S2CID 21610124. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ "Cambridge Dictionary". Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on August 19, 2019. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ Firth, John (2020). "Science in medicine: when, how, and what". Oxford textbook of medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-874669-0.

- ^ Saunders, J. (June 2000). "The practice of clinical medicine as an art and as a science". Med Humanit. 26 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1136/mh.26.1.18. PMID 12484313. S2CID 73306806.

- ^ Davis, Bernard D. (March 2000). "Limited scope of science". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 64 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1128/MMBR.64.1.1-12.2000. PMC 98983. PMID 10704471. & "Technology" in Bernard Davis (Mar 2000). "The scientist's world". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 64 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1128/MMBR.64.1.1-12.2000. PMC 98983. PMID 10704471.

- ^ James McCormick (2001). "Scientific medicine—fact of fiction? The contribution of science to medicine". Occasional Paper (Royal College of General Practitioners) (80): 3–6. PMC 2560978. PMID 19790950.

- ^ Breznau, Nate (2022). "Integrating Computer Prediction Methods in Social Science: A Comment on Hofman et al. (2021)". Social Science Computer Review. 40 (3): 844–853. doi:10.1177/08944393211049776. S2CID 248334446.

- ^ Hofman, Jake M.; Watts, Duncan J.; Athey, Susan; Garip, Filiz; Griffiths, Thomas L.; Kleinberg, Jon; Margetts, Helen; Mullainathan, Sendhil; Salganik, Matthew J.; Vazire, Simine; Vespignani, Alessandro (July 2021). "Integrating explanation and prediction in computational social science". Nature. 595 (7866): 181–188. Bibcode:2021Natur.595..181H. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03659-0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 34194044. S2CID 235697917. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Nissani, M. (1995). "Fruits, Salads, and Smoothies: A Working definition of Interdisciplinarity". The Journal of Educational Thought. 29 (2): 121–128. JSTOR 23767672.

- ^ Moody G (2004). Digital Code of Life: How Bioinformatics is Revolutionizing Science, Medicine, and Business. ISBN 978-0-471-32788-2.

- ^ Ausburg, Tanya (2006). Becoming Interdisciplinary: An Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies (2nd ed.). New York: Kendall/Hunt Publishing.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (May 10, 2006). "To Live at All Is Miracle Enough". RichardDawkins.net. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ a b "The amazing point is that for the first time since the discovery of mathematics, a method has been introduced, the results of which have an intersubjective value!" (Author's punctuation) —di Francia, Giuliano Toraldo (1976). "The method of physics". The Investigation of the Physical World. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–52. ISBN 978-0-521-29925-1.

- ^ Heilbron, J.L.; et al. (2003). "Preface". The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–X. ISBN 978-0-19-511229-0.

...modern science is a discovery as well as an invention. It was a discovery that nature generally acts regularly enough to be described by laws and even by mathematics; and required invention to devise the techniques, abstractions, apparatus, and organization for exhibiting the regularities and securing their law-like descriptions.

- ^ Popper, Karl R. (2002e) [1959]. "The problem of the empirical basis". The Logic of Scientific Discovery. New York: Routledge Classics. pp. 3–26. ISBN 978-0-415-27844-7. OCLC 59377149.

- ^ Diggle, Peter J.; Chetwynd, Amanda G. (September 8, 2011). Statistics and Scientific Method: An Introduction for Students and Researchers. Oxford University Press. pp. 1, 2. ISBN 9780199543182.

- ^ Wilson, Edward (1999). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8.

- ^ Fara, Patricia (2009). "Decisions". Science: A Four Thousand Year History. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-19-922689-4.

- ^ Aldrich, John (1995). "Correlations Genuine and Spurious in Pearson and Yule". Statistical Science. 10 (4): 364–376. doi:10.1214/ss/1177009870. JSTOR 2246135.

- ^ Nola, Robert; Irzik, Gürol (2005k). "naive inductivism as a methodology in science". Philosophy, science, education and culture. Science & technology education library. Vol. 28. Springer. pp. 207–230. ISBN 978-1-4020-3769-6.

- ^ Nola, Robert; Irzik, Gürol (2005j). "The aims of science and critical inquiry". Philosophy, science, education and culture. Science & technology education library. Vol. 28. Springer. pp. 207–230. ISBN 978-1-4020-3769-6.

- ^ van Gelder, Tim (1999). ""Heads I win, tails you lose": A Foray Into the Psychology of Philosophy" (PDF). University of Melbourne. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ Pease, Craig (September 6, 2006). "Chapter 23. Deliberate bias: Conflict creates bad science". Science for Business, Law and Journalism. Vermont Law School. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010.

- ^ Shatz, David (2004). Peer Review: A Critical Inquiry. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-1434-8. OCLC 54989960.

- ^ Krimsky, Sheldon (2003). Science in the Private Interest: Has the Lure of Profits Corrupted the Virtue of Biomedical Research. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-1479-9. OCLC 185926306.

- ^ Bulger, Ruth Ellen; Heitman, Elizabeth; Reiser, Stanley Joel (2002). The Ethical Dimensions of the Biological and Health Sciences (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00886-0. OCLC 47791316.

- ^ Backer, Patricia Ryaby (October 29, 2004). "What is the scientific method?". San Jose State University. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ Ziman, John (1978c). "Common observation". Reliable knowledge: An exploration of the grounds for belief in science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–76. ISBN 978-0-521-22087-3.

- ^ Ziman, J.M. (1980). "The proliferation of scientific literature: a natural process". Science. 208 (4442): 369–71. Bibcode:1980Sci...208..369Z. doi:10.1126/science.7367863. PMID 7367863.

- ^ Subramanyam, Krishna; Subramanyam, Bhadriraju (1981). Scientific and Technical Information Resources. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8247-8297-9. OCLC 232950234.

- ^ a b Bush, Vannevar (July 1945). "Science the Endless Frontier". National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ^ Schooler, J. W. (2014). "Metascience could rescue the 'replication crisis'". Nature. 515 (7525): 9. Bibcode:2014Natur.515....9S. doi:10.1038/515009a. PMID 25373639.

- ^ Pashler, Harold; Wagenmakers, Eric Jan (2012). "Editors' Introduction to the Special Section on Replicability in Psychological Science: A Crisis of Confidence?" (PDF). Perspectives on Psychological Science. 7 (6): 528–530. doi:10.1177/1745691612465253. PMID 26168108. S2CID 26361121. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ Ioannidis, John P. A.; Fanelli, Daniele; Dunne, Debbie Drake; Goodman, Steven N. (October 2, 2015). "Meta-research: Evaluation and Improvement of Research Methods and Practices". PLOS Biology. 13 (10): –1002264. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002264. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 4592065. PMID 26431313.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hansson, Sven Ove; Zalta, Edward N. (September 3, 2008). "Science and Pseudoscience". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Section 2: The "science" of pseudoscience. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Shermer M (1997). Why people believe weird things: pseudoscience, superstition, and other confusions of our time. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0-7167-3090-3.

- ^ Feynman, Richard (1974). "Cargo Cult Science". Center for Theoretical Neuroscience. Columbia University. Archived from the original on March 4, 2005. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ^ Novella, Steven (2018). The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe: How to Know What's Really Real in a World Increasingly Full of Fake. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 162. ISBN 9781473696419.

- ^ "Coping with fraud" (PDF). The COPE Report 1999: 11–18. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

It is 10 years, to the month, since Stephen Lock ... Reproduced with kind permission of the Editor, The Lancet.

- ^ a b Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003c). "Induction and confirmation". Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 39–56. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ^ Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003o). "Empiricism, naturalism, and scientific realism?". Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 219–232. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ^ Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003b). "Logic plus empiricism". Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 19–38. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ^ a b Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003d). "Popper: Conjecture and refutation". Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 57–74. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ^ Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003g). "Lakatos, Laudan, Feyerabend, and frameworks". Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 102–121. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ^ Popper, Karl (1972). Objective Knowledge.

- ^ Newton-Smith, W.H. (1994). The Rationality of Science. London: Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7100-0913-5.

- ^ Votsis, I. (2004), The Epistemological Status of Scientific Theories: An Investigation of the Structural Realist Account, University of London, London School of Economics, PhD Thesis, p. 39.

- ^ Bird, Alexander (2013). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Thomas Kuhn". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ Kuhn, Thomas S. (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-226-45804-5. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003). "Naturalistic philosophy in theory and practice". Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 149–162. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ^ Brugger, E. Christian (2004). "Casebeer, William D. Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition". The Review of Metaphysics. 58 (2).

- ^ Kornfeld, W; Hewitt, CE (1981). "The Scientific Community Metaphor" (PDF). IEEE Trans. Sys., Man, and Cyber. SMC-11 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1109/TSMC.1981.4308575. hdl:1721.1/5693. S2CID 1322857. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "Eusocial climbers" (PDF). E.O. Wilson Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

But he's not a scientist, he's never done scientific research. My definition of a scientist is that you can complete the following sentence: 'he or she has shown that...'," Wilson says.

- ^ "Our definition of a scientist". Science Council. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

A scientist is someone who systematically gathers and uses research and evidence, making a hypothesis and testing it, to gain and share understanding and knowledge.

- ^ Cyranoski, David; Gilbert, Natasha; Ledford, Heidi; Nayar, Anjali; Yahia, Mohammed (2011). "Education: The PhD factory". Nature. 472 (7343): 276–79. Bibcode:2011Natur.472..276C. doi:10.1038/472276a. PMID 21512548.

- ^ Kwok, Roberta (2017). "Flexible working: Science in the gig economy". Nature. 550: 419–21. doi:10.1038/nj7677-549a.

- ^ Woolston, Chris (2007). Editorial (ed.). "Many junior scientists need to take a hard look at their job prospects". Nature. 550: 549–552. doi:10.1038/nj7677-549a.